GOOD SAMARITAN STORY REIMAGINED (PART I)

By Akin Ojumu

The word parable comes from the root word “paraballo” (Latin) or in the Greek “parabole.” It’s a compound word from “para” which means “to come alongside or compare” and “ballo” which literally means “to throw” or “see” with.

Literally, paraballo (or parabole) means “a placing beside” (i.e., “to throw” or “lay beside, to compare”). It signifies “a placing of one thing beside another” with a view to comparison. It means something that’s “cast alongside” something else for comparison.

Variations of the word find meaning in many fields of human endeavor. For instance, in geometry, “parabola” refers to a comparison between a fixed point on a curve to a straight line, resulting in a parabolic curve.

Parables in the Bible are stories that are “cast alongside” a truth in order to illuminate that truth. Jesus employed parables as teaching aids, and he used them as extended analogies or inspired comparisons. They were earthly stories with a heavenly meaning.

Jesus spoke in parables to accomplish a two-fold purpose. One is to reveal the truth to those who longed for it. Secondly, Jesus spoke in parables in order to conceal the truth from those who were indifferent to it.

“Then the disciples came and said to him, “Why do you speak to them in parables?” And he answered them, “To you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given.” (Matthew 13:10-11).

Jesus ensured that His disciples understood the meaning of the parables he told by explaining it to them afterwards.

“When he was alone with his own disciples, he explained everything.” (Mark 4:34b).

Because the rest of the people were hardened in their hearts, the meaning of the parables was hidden from them. The eyes of their hearts were blinded so that they could not know the hope of His calling and were clueless to the riches of His glory.

“For the hearts of these people are hardened, and their ears cannot hear, and they have closed their eyes – so their eyes cannot see, and their ears cannot hear, and their hearts cannot understand, and they cannot turn to me and let me heal them.” (Matthew 13:15).

The Lord Jesus used parables to illuminate the truth of the Gospel in order that the understanding of those who believe may be enlightened. In the same vein, parables were told to conceal God’s truth from those who had already chosen to reject Jesus and the message of salvation.

As He went about His earthly ministry, the Lord Jesus told as many as forty parables. Some of the memorable ones include: Parable of the Sower (Matthew 13:1-23), Parable of the Mustard Seed (Matthew 13:31-32), Parable of the Lost Sheep (Matthew 18:10-14), Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13), Parable of Ten Talents (Matthew 25:14-30), and Parable of the Prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32) just to name a few.

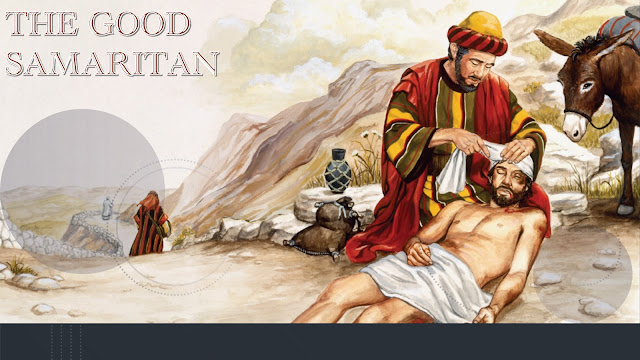

Of all the parables Jesus told, however, none is more familiar and/or popular than the Parable of the Good Samaritan. If there’s one Bible story that the secular world knows a whole lot about, it’s this one. So popular is the Good Samaritan story in pop culture that even the most Bible illiterate person on the street could give you a lecture on what it’s all about.

Over the centuries, several meanings and interpretations have been ascribed to the tale of the Good Samaritan by a hodgepodge of Bible scholars. Many of these interpretations are downright bizarre and outright wacky.

For instance, Origen of Alexandria, an early Christian scholar and theologian gave the Good Samaritan parable an allegorical interpretation:

“The man is Adam. Jerusalem is paradise. Jericho is the world. The robbers are hostile powers, demonic forces. The priest is the law. The Levite is the prophets. The Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience. The animal is the Lord’s body. The inn is the church, and the Samaritan’s promise of return is the Second Coming.”

Jim Wallis, the founder of the Sojourner, looked at the parable from lens of social justice:

“The Good Samaritan is a problem. It seems to promote short-term aid without addressing long-term justice. For example, what were the social conditions that led the man to abuse the wounded man, and was it a predictable outcome of a deeper societal illness? Was the Good Samaritan later inspired to engage the dilemma through advocacy…?”

Stay tuned. More to come...

Comments

Post a Comment